RETIRED headmistress May Lim dresses simply but her footwear is always fancy. She dons handcrafted sandals and shoes with beadwork she stitches.

“People asked me why I wear kasut manik (beaded shoes) to the market. I said why not. I have so many pairs of beaded shoes; I should wear and enjoy them rather than keep them at home,” says 78-year-old Lim, who is called Aunty May by all and sundry.

Like all Peranakan girls, Lim learnt needlework growing up. There were no formal classes; needlecraft was something that girls and women did at home.

“Our mother and aunts were always sewing and making beaded shoes. My chore as a young girl was to thread the needles for them. They would spare us some beads and we would make bracelets with them. I did cross-stitch and tapestry rather than beading but the method is similar,” says Lim who recalls her mother sewing frocks for her, her four sisters and their neighbours.

“She bought a big bale of cloth and just sewed the dresses. That’s how I learnt to sew. I just trace the old dress on the material and made sure there are three holes – one for the head and two for the arms,” recalls Lim half in jest.

But in those days, needlework was a requisite skill that Lim acquired through observation and some practice. She left Penang and furthered her studies in Kuala Lumpur, and continued doing needlework.

“In college, I used to earn extra money tatting lace collars for the expatriate women in Kuala Lumpur. When I started teaching, I used to tailor my own qipao as it was cheaper than buying them,” recalls Lim who eventually returned to teach in Penang. Her last posting was as headmistress at Convent Light Street before opting for early retirement in 1994 to care for her parents.

After she retired, she was roped into social work which included training single mothers in handicraft as an income generating skill. She taught women how to do patchwork and sew bags, and she would then sell the bags to raise funds for them.

Eventually Lim started teaching students how to make beaded shoes. There are some Penangites who still know how to sew beaded shoes, but Lim is one of the rare few who is teaching the craft. She conducted classes under the Penang Heritage Trust for a decade, and continues to do so at the State Chinese Penang Association.

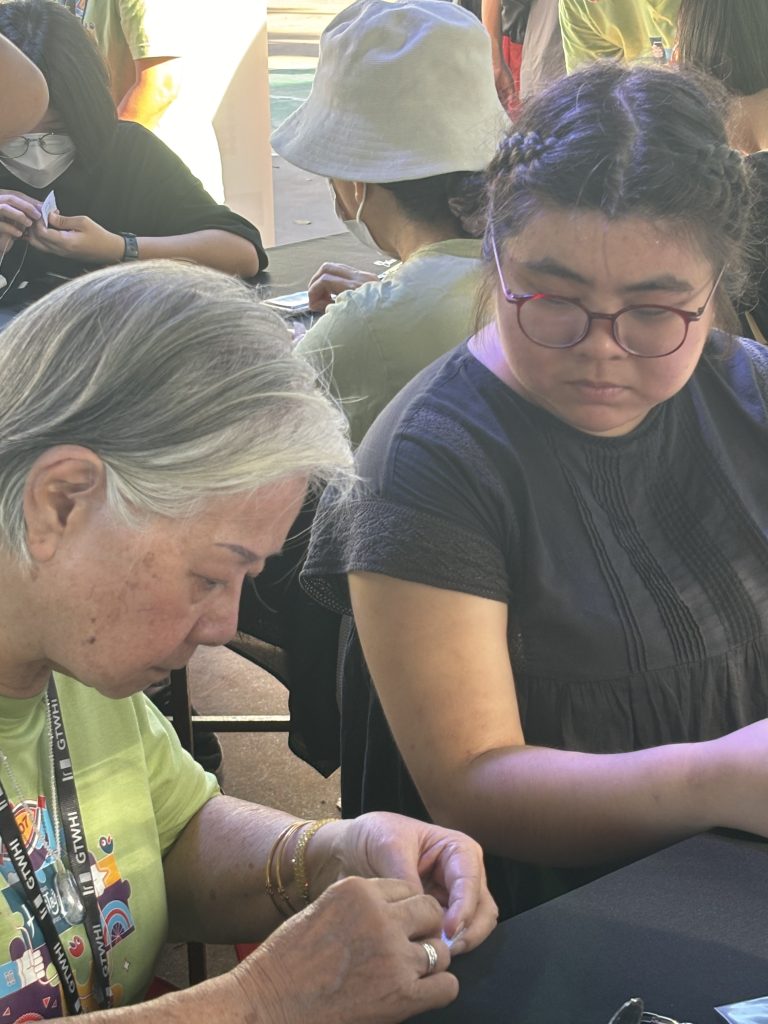

At the George Town Heritage Celebrations last month, Lim and her team of volunteers were at hand to introduce the craft of Nyonya beading to visitors, and offered visitors a chance to learn the craft. Her tables were swarmed and filled with so many people diligently sewing on tiny beads.

“We put together 500 samplers for this event. Usually we’d do 100-200,” says Lim who is regarded as a custodian of a heritage craft, with a mission to preserve the art. Lim is a recipient of the Living Heritage Treasures Award (LHTA) from the Penang Heritage Trust for her work in the craft of Nyonya beading. She is a tad bemused because growing up she was a self-professed tomboy.

“I ran around and cycled my father’s huge bicycle. We fished and played catapult. My childhood was full of activities and so much fun,” recalls Lim who is admittedly a little pained seeing children bent over their devices rather than out playing. She’d tell you that young children and teens are also interested to learn beading.

“When my niece saw the kasut manik I wore for a wedding, she said she wanted to learn and so I taught her. And she completed her work.

“I have also taught beading at a boy’s school and they also learnt. But I modified the lesson. We made beaded badges of letters that they could sew on to their caps or knapsacks.”

As proud as Lim is of the tradition of Nyonya beadwork, her approach is not dogmatic or clouded by nostalgia.

She taught herself to design nyonya beaded shoe patterns on graph paper and on Excel, and encourages her students to come up with their own original designs rather than making “another gold fish manik shoe”.

Lim’s experience as a teacher also influences how she passed on the traditional craft. She has defined the techniques needed – how to bead in a straight line, how to do the toe cover and how to sew the curve. Each student completes two pairs of shoes at these levels but there is no set time limit for completing these assignments.

Above all, Lim values the intrinsic benefits of being absorbed in needlecraft.

“When you do beading, you have to focus, bead after bead. It cultivates patience and gives you a sense of accomplishment when you finish a piece. I have taught students in high stress jobs who find beading therapeutic. I also teach senior citizens beading because it’s good for them,” says Lim who also teaches other handicraft such as making bags with recycled materials.

These days, Nyonya beaded shoes fetch hundreds of ringgit and learning to make kasut manik can be a good source of income even though it takes weeks to finish a piece as it’s intricate detailed work. A pair of kasut manik could contain up to 20,000 beads.